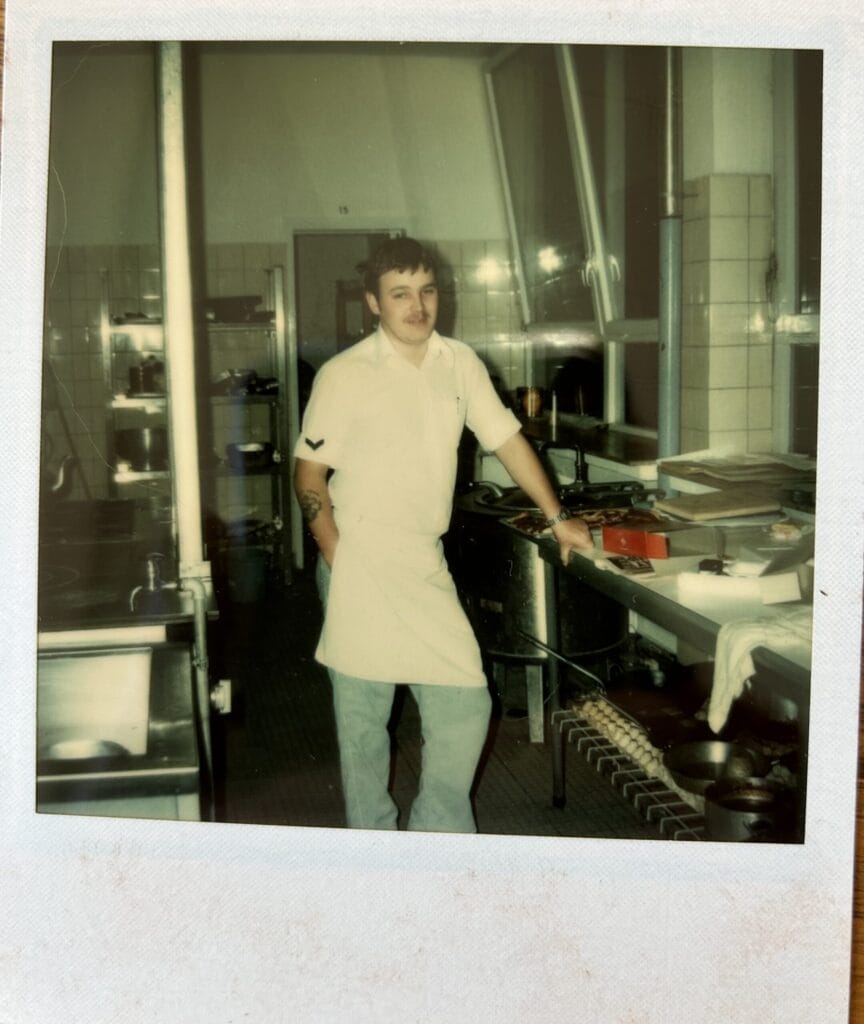

Jamie’s story

Jamie Hull is an extraordinary man. Not just because of events that have befallen him, but what he was before those events and everything he has done since. King Edward VII’s Hospital was proud to help support him after he recently broke his arm, but this is only a small part of Jamie’s incredible journey.

From force to force

“It all started at the Freshers Fair,” says Jamie as he starts his story. “I’d been in the police but returned to university aged 25. At the fair, I got talking to a guy from the army and he said, ‘You’re the kind of person we’re looking for’. I’d never considered the army, but I warmed to him so we chatted for a while.” Before he knew it, Jamie was on a weekend of selection for the Cambridge University Officer Training Corps. And he loved it.

“They’re a pretty motivated mob so it was pretty cut-and-thrust,” he says. “But it suited me.”

And so Jamie – still a part-time student – trained for a year, including P Company (the parachute regiment) which he passed alongside full-time soldiers. This took him on to Royal Military Academy Sandhurst which he also passed, to become a Second Lieutenant. “I must have been doing something right, because I then received a recommendation for the UK Special Forces.”

Jamie describes the opportunities with this new unit as “second to none” – travelling the world with the 21 SAS (Reserve), from the Arctic to the mountains to the jungle. From 2003 he spent five years on the squadron, “parachuting, signals and using lots of cutting-edge communications technology – even satellite communications. “But I was still only soldiering on the side,” explains Jamie. “I considered doing it full-time, but I also had another ambition…”

Learning to fly

“My grandfather trained as a pilot at the end of the Second World War. As a young child, he would tell me stories about flying and he would take us to Luton Airport to go plane spotting. I loved it: the noise of the jets and the smell of the kerosene.

“I thought: one day, I’d like to do this myself. I want to fly.”

As you might guess, Jamie is a man who doesn’t let ambitions gather dust. And so, in his early 30s, he decided to go to flight school. He applied for an American Visa, passed the rigorous checks and headed to Florida to start the programme.

Fire in the sky

After a month, Jamie had become a pilot in command (PIC) – able to pilot a light aircraft solo

“I was keen to get my flight hours up,” says Jamie. “I’d just had lunch, got my permissions, checked radar and was ready to head up.”

Jamie hadn’t been in the air long when he noticed that the engine was on fire. “I looked out of the left window and saw a thin streak of yellow flame coming from the engine – just behind where the propeller was spinning. ‘Christ’, I thought, ‘this is real engine fire. This is no drill. I have to get this aircraft down’.”

Jamie steered in and out of the wind as he returned to approach the runway, but, as he turned into wind and saw the runway, he could see that the fire had breached the cockpit. “I looked down and I could see the fire building up around my feet and ankles.”

He descended quickly – 800 feet, 700 feet – but as he did so, the fire only grew within the small two-seater cockpit. At 500 feet up, the fire was lapping his midriff. Jamie assessed that the growth rate of the fire and the distance from the runway meant he wouldn’t make it. I knew that I wasn’t going to be able to land the plane in the conventional sense: land it on the runway, bring it to a stop and exit the cockpit.”

Unless…

“I had a light-bulb moment,” he says. “I’m going to ditch. I aimed away from the runway that was off in the distance and I headed towards a grassy stretch. I started the emergency procedure: I turned the ignition off, the red switch for magnetos off, I turned the lights off, the strobes off, the fuel pump off and the master switch off.

“I knew it well because I’d practised it so many times with instructors.

Having turned everything off, Jamie is now gliding in, using various tactics to slow the plane down.

100 feet above the ground, flames lapping his chest, Jamie removed his headset, unbuckled his harness and opened the left-hand canopy door.

60 feet, 50 feet…

“The flames were now lapping my face. I’m hyperventilating and breathing out of the side of my mouth in an effort to protect my airway. I closed my right eye to protect it, but needed my left eye to see where I was going.

“I got onto the seat.”

40 feet, 30 feet…

“At 20 feet off the ground, I climbed through the open door and onto the left wing. At about 15 feet, I was doing about 30 knots. I’m out of the cockpit but now I’m still being lashed by the flames that are coming off the propeller.

“I kept my eyes on the horizon and I leapt.”

Jamie was an experienced parachute jumper, so he snapped into the British Army exit position: bringing his knees up and together and putting his hands above his head.

“I landed like a sack of spuds, rolled and smashed my face into the grass.

“I then watched the plane crash land some 70 feet away. After the crash, the plane exploded and while I was outside of the blast radius I still felt the shockwave which literally took my breath away – I couldn’t breathe. When that subsided and I caught my breath, I managed to crawl 15 feet further away from the intense heat of the explosion and the burning wreckage.

“That’s when the pain hit me like a sledgehammer – indescribable, pure and total pain.”

Jamie’s injuries were extensive and profound. He suffered a bilateral nasal fracture, super orbital eye socket fracture of both eyes, a hyperextended finger, impacted two ribs, a clavicle fracture, a ruptured colon and a lacerated liver which was haemorrhaging and bleeding. Jamie had also suffered 63% third- and fourth-degree burns – “the latter being when the burns are down to the bone. My shins bore the brunt of that – spending the longest time in the flames before I was able to get out of the fire.”

This is how they work out your probability of survival in cases like this: add your age to the percentage of the body surface burned. What remains is your chance of survival. In Jamie’s case, the maths looked like this: 32 (years old), plus 63 (percentage of surface burned), is 95. Jamie had a five percent probability of survival.

“I lay there in despair. I knew it was bad. I knew my life would never be the same again. Then I became resigned to the fact that I wasn’t going to make it. I knew I didn’t have long. I was dying.

“Then I heard the sirens.”

Rescue operation

Emergency services quickly arrived on the scene and Jamie was airlifted to Orlando Regional Health Centre. Clinicians quickly put Jamie into a medically induced coma where he remained for six months while surgeons operated and his body started to heal.

Jamie was repatriated to Chelmsford Central Burns Unit in Essex where he remained in intensive care before being transferred to Stoke Mandeville Hospital in Buckinghamshire for 17 months.

Overall Jamie was an in-patient for two years. Over the course of the following seven years, he had 64 surgeries under general anaesthesia.

“The cost of my care in the US came to $2.8m alone.”

Rise…

“I slowly crawled back from the brink,” says Jamie of his rehabilitation. “It wasn’t just physical healing, but getting myself mentally well again.”

Not only did he teach himself to write again and walk again but Jamie has since gone on to run marathons, do long-distance cycling, and take part in the Invictus Games. He has also led expeditions, become a diving course director with PADI and gone on to write his autobiography Life On A Thread for Penguin.

Jamie is a truly astonishing person, and hearing his story first-hand is a moving experience in itself. It is no surprise that, in addition to his many achievements, he has also gone on to become a motivational speaker working with schools, businesses and the fire service.

“Life was going well again.”

…and fall

16 years later, in March of 2023, Jamie was skiing in Norway.

“I was involved in a freak incident and had a high-speed fall in which I broke my humerus – and it was a nasty break.”

The NHS was still reeling from COVID19 and the waiting list for treatment was long.

“I was out of action and it was tough on me – it was depressing and I was struggling,” says Jamie.

Centre for Veterans Health

After a few months, the SAS Regimental Association helped Jamie get in touch with Orthopaedic Surgeon Peter Riley, here at King Edward VII’s Hospital. Peter spoke to and examined Jamie before recommending a titanium plate.

“I asked how much it would be to have the procedure done privately because I just couldn’t wait for the NHS. It had been four months with this bone split in two, swinging around. I was desperate. But it was too expensive for me to go private.

Peter told Jamie about the Centre for Veterans Health there at King Edward VII’s Hospital, explaining that he could apply for financial support and that he, Peter, would support his claim. Jamie applied and the panel quickly came back to him to inform him that the Centre for Veterans Health would provide a hundred percent of the cost.

“I was amazed. It meant the world to me.”

Jamie came into King Edward VII’s Hospital for surgery on July 13th 2023. The surgery was a success, Jamie was discharged and within five days he was up to his old tricks, this time doing the International Four Days Marches Nijmegen in the Netherlands – which involves marching 50 kilometres a day for four days. Jamie adds that: “I still had the vacuum pump with me, pumping fluid out of the wound.

“The speed with which it all happened was remarkable: from application to surgery and discharge was about five weeks. And it was a big surgery. It was a bespoke piece of titanium and eight screws. State of the art. It was incredible.”

“I’m very grateful to KEVII for all the great work they do for vets like me. Unfortunately, not every vet will be successful in their application. That’s why I want to raise awareness and help to raise money for people like me.”

Jamie generously came to tell his story to a rapt audience of 300 people at a recent Centre for Veterans Health fundraising event in London – helping to raise more than £30,000.

“After my accident in Florida I had built a very active life and my skiing accident stopped all of that. I had lost my confidence – I was broken and depressed – but through genuinely world-class surgery, care and financial support, KEVII has made me the double comeback kid.”

King Edward VII’s Hospital and the Centre for Veterans Health are proud to help Jamie and veterans like him, and every day humbled by their tenacity, stoicism and strength of spirit.

More information

- If you are a veteran in need of support, or have any queries about the assistance we can offer you, please contact Caroline Dunne, Centre for Veterans Health Coordinator: cdunne@kingedwardvii.co.uk

- Find out more and apply for a military grant

- Did you know all Service or ex-Service Personnel (including reserves) without medical insurance are entitled to a 20% discount on their hospital bill. It also extends to their spouses/civil partners and includes widowers and widows.

- Find out more about Jamie at jamiehull.co.uk and you can buy his amazing story, Life On A Thread, here.

Help support our charitable work with Armed Forces veterans.

Are you inspired by Jamie’s story and wish to make a donation to the Centre for Veterans’ Health?

100% of donation to the Centre for Veterans’ Health, go directly to support veterans.

Help support our charitable work with Armed Forces veterans.

Are you inspired by the stories you’ve read here and wish to make a donation to the Centre for Veterans’ Health?

100% of donation to the Centre for Veterans’ Health, go directly to support veterans.

Since 1899 King Edward VII’s Hospital has supported members of the Armed Forces. We continue to uphold this commitment today.

For information, contact Caroline Dunne - Coordinator of the Centre for Veterans’ Health, at cdunne@kingedwardvii.co.uk.

All Service or ex-Service Personnel (including reserves) without medical insurance are eligible for a 20% discount on hospital fees. This also applies to their spouses, civil partners, widows, and widowers.

More stories

If you require surgical treatment, our world-famous centre of excellence is able to treat the full spectrum of knee conditions and complaints.

You can be seen by a specialist quickly and at a time that suits you, with same day appointments often available.